Muscles

Lungs assembly

My two lungs are like two balloons contained in something like a lubricated and inflatable bag. No muscles are directly attached to my lungs themselves; the muscles connect to the containing bag.

A vacuum is created when the attached muscles pull the bag out. Because of the vacuum, the pressure inside the lungs drops, and the air is sucked in. Once my lungs get filled with air, the pressure equalizes.

From now on, when I refer to the ‘lungs,’ it will include the containing bag and the two lungs inside.

Three primary muscle systems are directly attached to the bag, containing my two lungs:

- Diaphragm muscle.

- Ribcage muscles.

- Chest muscles.

The diaphragm muscle

My diaphragm is a relatively slow-moving muscle. It’s like a sluggish yet powerful locomotive that drives my breathing, and together with the heart, it propels my life.

The diaphragm connects to my lowest ribs and supports my lungs from the bottom. It creates a definite division of my body into two parts. One part is above my diaphragm, and the other part is below. Above the diaphragm, I have my heart and lungs. Below, I have my liver, kidneys, spleen, pancreas, digestive organs, and others. The diaphragm is also attached to my spine and is affected by my spine’s flexibility and mobility. In addition, a busy channel passes through my diaphragm, including a network of nerves, a food pipe, and blood pipes.

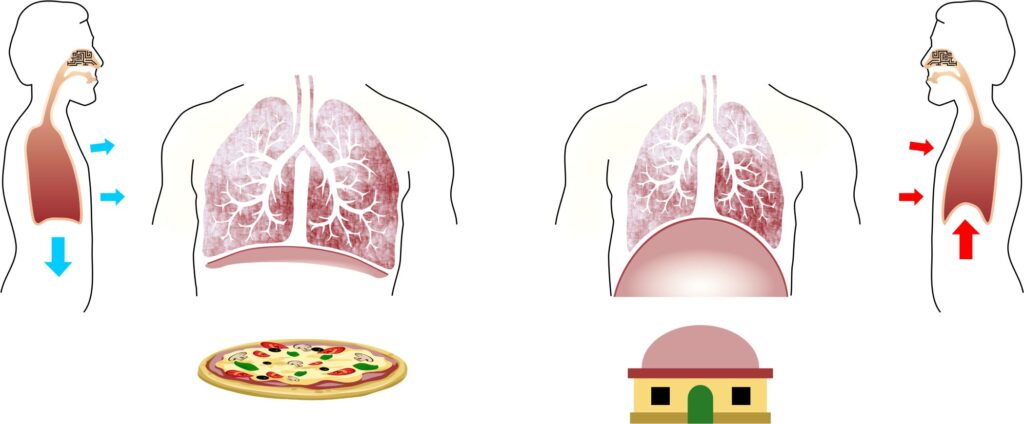

The active part of my breathing occurs as I inhale, where Air gets drawn into my lungs. My navel moves away from my spine as my belly becomes rounded, assuming the shape of a watermelon. Simultaneously, my diaphragm muscle flattens and pulls downward, eventually taking the shape of a pizza. These changes help create a vacuum in my lungs, and Air flows into them as my chest cavity expands.

The passive part of my breathing occurs as I exhale, where Air flows out of my lungs. My navel moves toward my spine as my belly draws inward. At the same time, my diaphragm muscle relaxes and ascends into the shape of a dome. These changes often make my chest cavity smaller and assist in expelling Air from my lungs.

Down to the bottom

When I engage my diaphragm effectively, the Air flows to the bottom of my lungs, which allows me to:

- spread Oxygen over a more significant number of exchange bubbles, thus increasing absorption;

- keep the lower bubbles active;

- maintain lung elasticity;

- and exercise diaphragm muscle.

Failing to use my diaphragm effectively when breathing may lead to losing bubble exchange functionality at the bottom of my lungs. In addition, when my lungs are not pulled and pushed, they may lose elasticity and become stiffer, leading to decreased respiratory performance.

When my diaphragm is active—moving up and down—it has physical contact with a few of my vital organs. The up-and-down movement gently presses on these organs, massaging them every time I inhale and exhale. Swollen organs close to the diaphragm may restrict it from moving freely and may cause movement distortion.

It’s essential to have enough space in the abdomen for the diaphragm to move freely. When inhaling in an upright posture, the diaphragm moves downward, pushing the organs into the lower part of the body. That allows my lungs to expand and Air to flow in. When exhaling, the diaphragm moves upward and presses on my lungs from the bottom, thus helping to expel the Air. A straight spine allows deeper descent and higher ascent of the diaphragm.

Engaging the diaphragm while breathing makes it easier for my heart to pump blood, thus reducing my blood pressure. When the diaphragm moves up and down at a wide amplitude, my ‘breathing app’ gets an acknowledgment from my diaphragm that I’m not in a threatening situation. Furthermore, proper diaphragm movement relaxes the digestive system and improves elimination.

Some waste products in my body have no active pumping system for expulsion and cleaning. When the diaphragm moves up and down, it helps clear lymph waste, facilitating detoxification. When something goes wrong, and my body needs to expel by vomiting, my diaphragm muscle assists by pressing on the stomach cavity from within.

We humans haven’t fully completed our evolutionary transition from four to two legs. As a result, my body struggles to balance on two long ‘sticks’ (my legs). The diaphragm muscle takes part in my body’s efforts to keep balance.

My eyes are at the front of my head, so intuitively, when I visualize breathing with my diaphragm, it appears as if my abdomen is going in and out. However, it’s essential to understand that the diaphragm should expand and contract in all directions, encompassing a 360o movement. Perceiving it as an all-around muscle may facilitate more efficient diaphragm muscle activation.

How I trace my diaphragm in 360o

- Sit on a chair or stand up.

- Place the fingertips of both my hands where my ribs meet, at the base of my breastbone.

- Trace down my ribcage on each side of my body with my fingertips.

- Continue until I reach the lowest points of my bottom ribs. That’s about half of my diaphragm’s circumference.

- Continue tracing the second half by following my ribs around until my fingers reach my backbone (spine).

The ribcage muscles

My ribcage muscles are a group of smaller muscles compared to the single diaphragm muscle. They function as small body ‘motors’ which move my ribcage and pull my lungs mainly from the sides. Between every rib, which is attached to my lungs, there are muscles. It’s a bit like piano keys, where the white keys are the ribs, and the black keys are the muscles. My ribs are meant to protect my lungs from mechanical shocks, but it is just as important that they are flexible and can move freely. The free movement depends on the elasticity of both my ribcage muscles and the ribs themselves.

My diaphragm becomes less dominant during intense physical activity, and the driving force of breathing passes on to my ribcage muscles. Like the diaphragm, proper ribcage inflation occurs by expanding the front, back, and sides in 360⁰ degrees, similar to the opening of an umbrella.

The way I Inflate my ribcage 360⁰ degrees:

- I sit on a chair or stand up.

- Start by placing my fingers on the ribcage ‘piano’ and feel both the ribs and the muscles between them.

- Place one palm on each side of my ribcage and then create a bit of resistance by slightly pressing from the sides.

- While I inhale, my palms move away from my spine, and when I exhale, towards my spine. There is an equal movement of my palms on both sides of my body.

- Then I place one palm at the front of my body, under my lowest ribs, and the back side of my other hand is on my back. I make sure that at least my finger knuckles are touching my back. Both palms are parallel to each other.

- While I inhale, my palms move away from my spine, and when I exhale, towards my spine.

The chest muscles

My chest muscles are attached to the top of my lungs. They are located above my nipple line, below my collarbone, and can pull and push my lungs from the top. Compared to my diaphragm and ribcage muscles, chest muscles are restricted and have less room to expand, but they can work intensively.

Chest muscles inflate 360 degrees, but since the inflation is more subtle, the all-around opening is more difficult to sense.

The way I sense my chest inflation:

- I sit on a chair or stand up.

- Start by placing the tips of my fingers on the two sides of my collarbone.

- Then I ‘step’ down from each collarbone, ensuring my fingers are perpendicular to my body.

- When I inhale, my fingers move away from my body; when I exhale, my fingers move back toward the body.

Secondary breathing muscles

I have a secondary ‘backup’ system of muscles to support my breathing during exertion: my neck, shoulders, and abdominal muscles. These auxiliary muscles were not meant to be involved in my breathing during rest. Engaging my secondary muscles without physical exertion may weaken my primary breathing muscles and get them out of sync. When I activate my secondary muscles out of sync with my primary breathing muscles, tension may build up in my neck, shoulders, or stomach.

The exclusive use of my primary breathing muscles while breathing results in relaxing feedback signals to my ‘breathing app.’ However, when I activate my secondary and primary breathing muscles during relaxation, signals change from relaxing to alerting.

My abdominal muscles are not involved directly in breathing; they help stabilize my body. One of the stomach muscle’s essential functions is to hold my soft inner organs in place and create a protective corset to shield my organs. These muscles also regulate the internal pressure in my stomach. Activating my abdominal muscles out of sync may restrict the movement of my diaphragm.